At the Intersection of Animism & Attachment: Re-introducing Ecological Attachment Theory

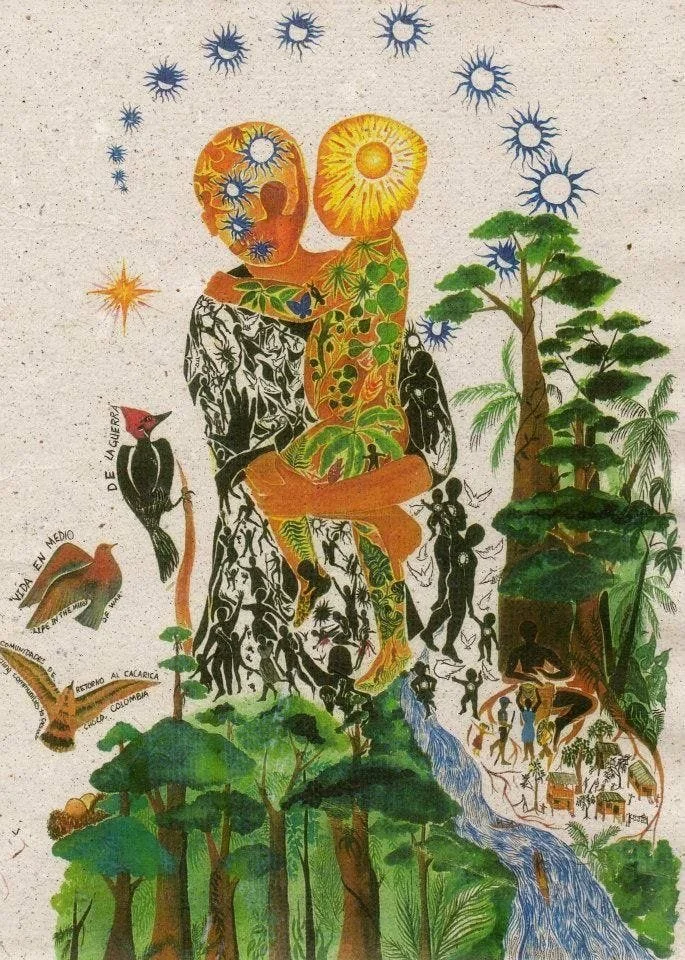

“Eco-artist Ana Tierra (Ana Maria Vasquez) uses her art to express the wonders of life on Pacha Mama (Mother Earth)”

Introducing Ecological Attachment

Over the past few years, I’ve spent a lot of time contemplating the intersections of attachment theory and human + ecological relationship. I’ve found these explorations to be really helpful in defining this relationship, as well as helping address how historical trauma, colonialism, and capitalism have shaped and transformed our connection to the Land.

It is through broadening our web of attachments to include our natural environments that provide us with deeper and more meaningful healing on individual & communal levels. Ultimately I don’t think communal health can exist without repairing our relationship with the ecological community around us.

I’ve used these concepts to help provide a foundation for earth-based energetic healing, working off the basis that we cannot reconnect with the Earth without addressing our land-based traumas and colonially-informed energetic blueprints. These blueprints have been carefully articulated to make those of us who live an urban/modern life more and more disconnected from the Earth, and in turn more and more dependent on man-made infrastructure and systems of production and consumption. The continuation of this paradigm (while simultaneous progressive degradation of our ecological environments on which we are dependent) are dependent upon this severance from the Earth.

Working with the energies of the land, as well as forming new energetic pathways that reinforce this connection between body + community + land help us form a secure attachment with the land. What healing is possible as we turn to nature as our model for balance, embodiment, and resilience? How can being securely attached to nature and being in healthy relationship with the land help inform our human-to-human relationships?

What is Attachment Theory?

“Attachment theory is a lifespan model of human development emphasizing the central role of caregivers (attachment figures) who provide a sense of safety and security.

Attachment theory hypothesizes that early caregiver relationships establish social–emotional developmental foundations, but change remains possible across the lifespan due to interpersonal relationships during childhood, adolescence, and adulthood” (McLeod, Simply Psychology).

The concept of attachment theory helps us understand the connection between safety & relationship as a foundation for healthy relational dynamics throughout one’s life. It is often emphasized that any fracturing, abandonment, or lack of safety with attachment figures in our childhoods can lead to the development of dysfunctional attachment styles - essentially different approaches to coping with fear, instability, and other unwanted relational outcomes.

Place and Land-Based Attachment: decolonizing attachment theory to broaden the definition of attachment figures to include Place and Land

I find that attachment theory is a useful and insightful tool for helping us understand our interpersonal relationships, and has had significantly positive impacts on how I understand my own relationship dynamics. What attachment theory lacks is something that Western psychology, and Western culture in general, typically excludes - our relationship to the Land, both personally and collectively/culturally, and the impact our land-based relationships have on our development as people and as communities.

It is no secret that cultures all around the world structure their webs of connection in ways that emphasize community over individual, many of which also include the ecological community - as a spiritual entity, or entities - within their web. I personally believe that it is at the intersection of attachment theory + animism where Ecological Attachment Theory sits.

For example, in traditional Japanese culture, place is something we as humans are constantly in relationship with. The home/place of dwelling, is understood to be its own kami, or spirit. Additionally, there are many other spirits that people will typically invite into their home to ensure safety from malevolent spirits that reside outside the home, keep the family healthy, and so on. My obachan (grandmother) had komainu statues both inside and outside the home; komainu are a “lion-dog” found in Japanese mythology, known for guarding the entrances of shrines from evil. Because the home is understood to have its own spirit, it is apart of daily life to tend to the home, clean it, and take care of it so that the spirit will be happy. In contrast, homes that are abandoned have a whole different spiritual trajectory of their own, tsukumogami, kami spirits of homes and objects that have been abandoned. The concept of these place-based spirits is an extension of land-based spirits, which proliferate and vary region to region.